The Mozart Myth: Why playing music matters more than just listening

You’ve probably heard the claim: pop on a Mozart CD and your baby (or you) will get smarter. That idea — the “Mozart Effect” — took off in the 1990s and stuck in parenting blogs, product marketing, and urban legend. The truth is messier and much more interesting: brief listening to classical music may give a tiny, short-lived boost in arousal or mood, but decades of neuroscience now show that active music-making and long-term musical training shape the brain in meaningful, lasting ways. The work of Dr. Nina Kraus and colleagues (and many others) helps explain why practice beats playback.

Listening vs. doing: two very different experiences for the brain

When you passively listen to music you engage reward circuits, emotions, and attention — that’s pleasant and sometimes motivating. But learning to play an instrument or participating in sustained music classes recruits a much broader set of brain systems: fine motor control, sustained attention, working memory, auditory perception, and social coordination.

Over time those repeated, effortful experiences lead to measurable neuroplastic changes — the brain literally tunes itself to sound in ways that passive listening does not produce. This is a central message of Kraus’s lab: musical engagement (making music) changes the way the nervous system represents sound.

What Kraus’s Frontiers in Psychology study found

In Frontiers in Psychology, Kraus and coauthors reported on community-based music engagement programs and their effects on children’s auditory skills. The study found that children who participated in consistent, structured music classes showed improvements in neural processing of sound, including better encoding of speech cues and improved ability to hear in noisy environments — outcomes linked to later reading and communication success. Those kinds of neural gains are associated with active training over time, not with a one-off session of classical music. In short: community music-making sparked neuroplasticity and real benefits for listening in complex environments.

What active music-making improves (and how it translates to everyday life)

Research following children and adults who take music lessons or participate in ensemble programs shows improvements in:

- Neural encoding of speech sounds and pitch — helping with speech-in-noise comprehension.

- Auditory attention and working memory — skills that support classroom learning and communication.

- Language and reading-related abilities, especially when music training starts in childhood.

These are concrete, functional gains — not abstract claims about instant IQ increases. They come from repeated, effortful practice that strengthens the auditory system’s fidelity and the brain’s ability to prioritize signals in noisy environments.

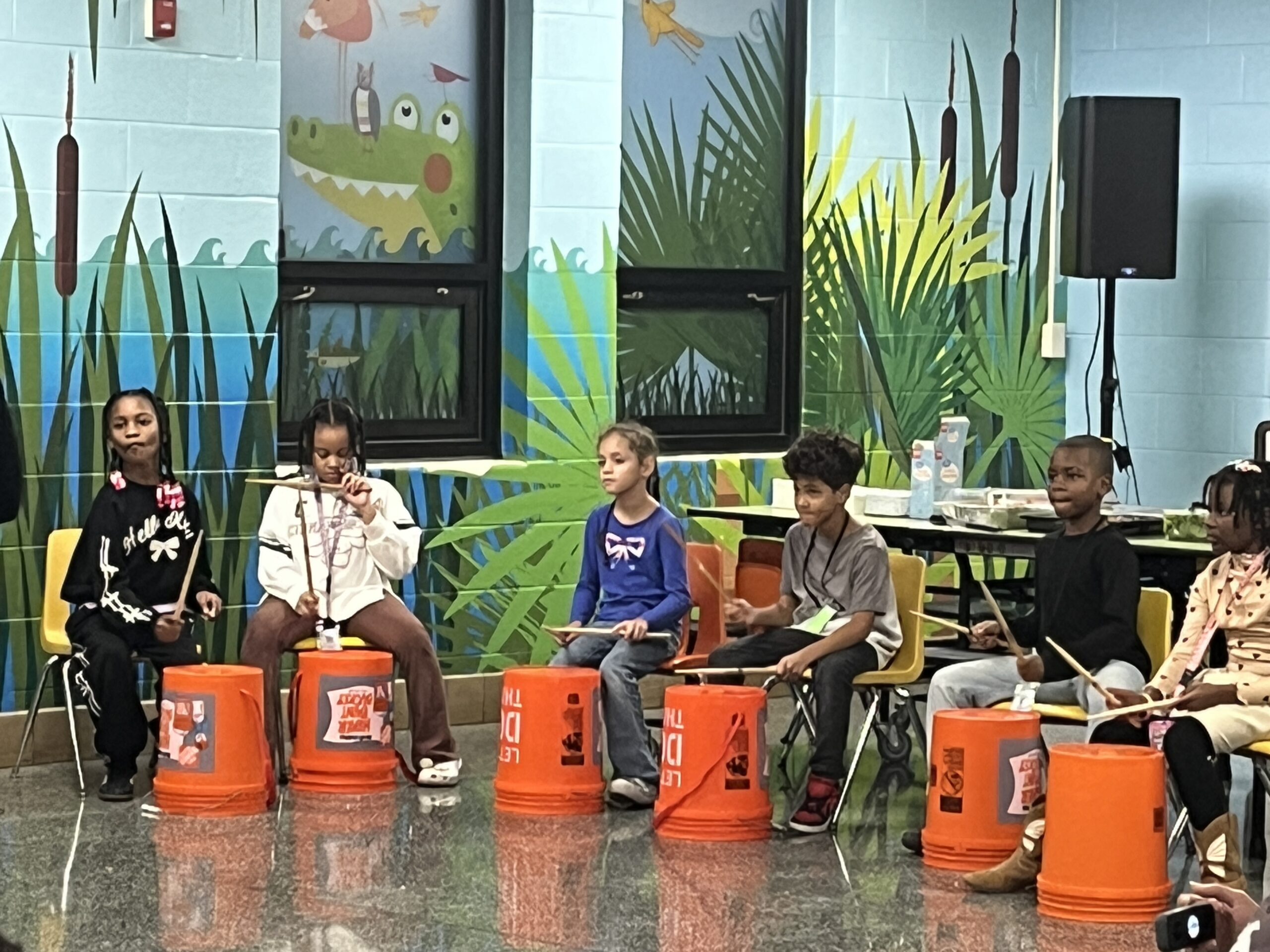

If your goal is to boost children’s language, listening, or academic readiness, invest in active music experiences: group music classes, instrument lessons, choir, or community ensembles. Programs like Soundscapes that emphasize regular practice, social music-making, and progressive skill-building are the ones linked to neurophysiological and behavioral improvements. Simply turning on classical music in the background is nice, but it’s not a substitute for body-and-mind involvement in music.

Sources:

• “Engagement in community music classes sparks neuroplasticity and language development in children from disadvantaged backgrounds” by Nina Kraus, Et al. (https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01403/full)

• “How Music and Language Shape the Brain” by Julie Deardorff (https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2015/12/how-music-and-language-shape-the-brain)

• “After the ‘Mozart Effect’: Music’s Real Impact on the Brain” by Naomi Lewin (https://www.wqxr.org/story/after-mozart-effect-music-impact-brain)

Music, and specifically playing an instrument, has innumerable positive effects on the brain.

Check out this video from TedEd for a quick overview on the science:

Soundscapes works hard to back up these claims with data. A generous grant from the Bernardine Franciscan Sisters Foundation supported the development of a customized evaluation tool by Dr. David Dirlam, a nationally recognized specialist in learning assessment methodologies. Dr. Dirlam created a rubric to measure each student’s progress along nine separate musical and behavioral dimensions. In addition, he designed a parent survey to assess family expectations and results at the start and end of each school year. Also, thanks to our partnership with Newport News Public Schools, we have access to data on economics, demographics, disabilities, attendance, behavior infractions, and SOL passing rates for our students. This allows us to understand and evaluate the whole child in context.

Using these tools, Soundscapes can confirm that we are achieving our goal of providing value to students in both behavioral and musical skills.

As this chart shows, students living in poverty start out behind their peers, but after time in the program, the achievement gap is eliminated.

This chart indicates that social/behavioral growth is happening at nearly the same rate as musical growth, showing that Soundscapes is successfully teaching life skills through music education.

If you are interested in learning more about Soundscapes’ curriculum and rubric, contact Program Director Rey Ramirez at rramirez@soundscapeshr.org